Gwen Wilkinson

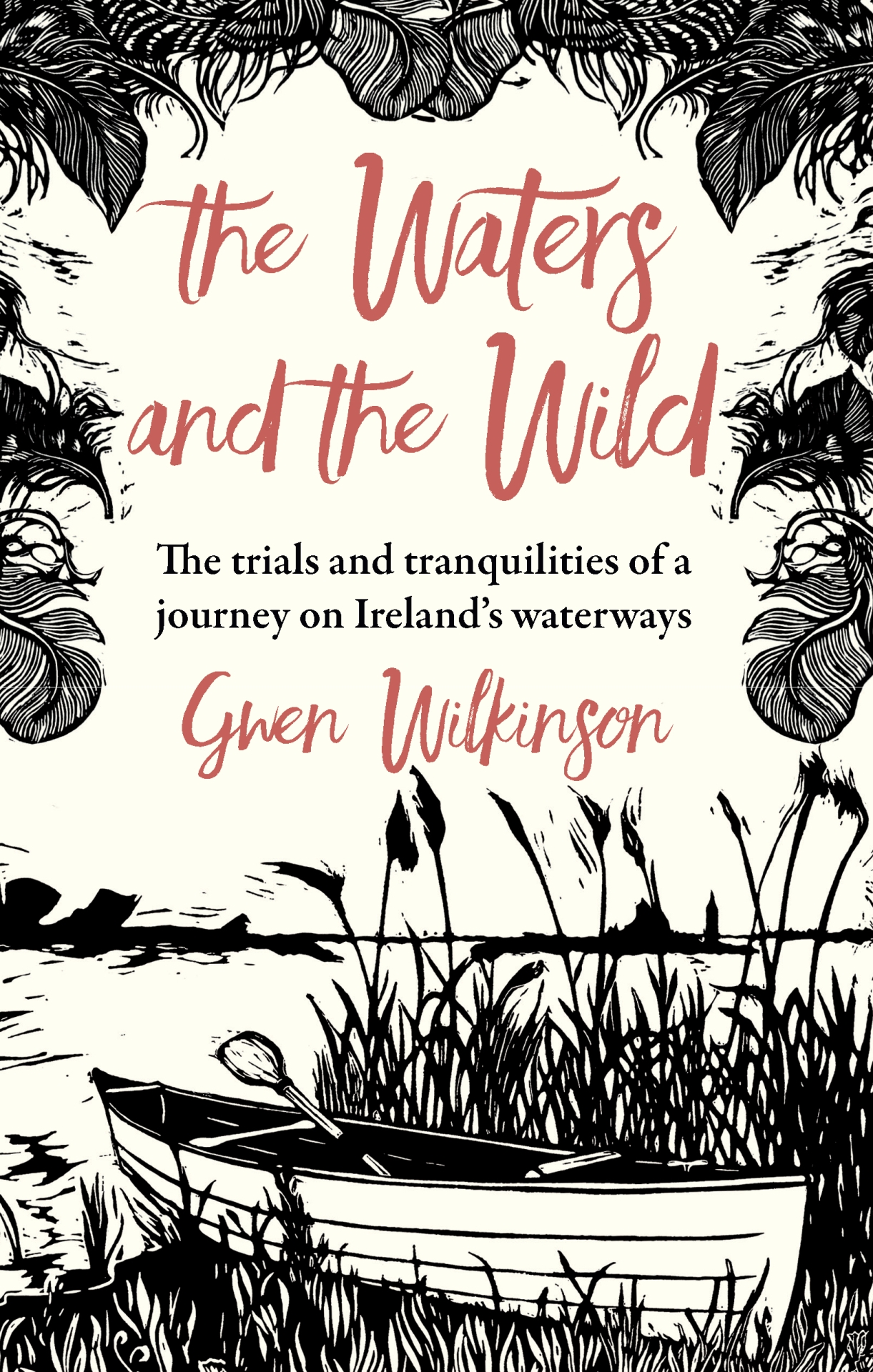

Gwen Wilkinson set out from the shores of Lough Erne and navigated a 400km journey to the tidal waters of the River Barrow in Ireland.

More than just a travelogue, ‘The Waters and the Wild’ explores the interwoven histories of the people and wildlife that shaped Gwen’s journey.

As the adventure unfolds, she also shines a light on pioneering women who have left their mark on Ireland’s landscape – both natural and cultural.

The following is what she wrote about County Kildare

The river whisks me past a dizzying time-lapse of Athy’s architectural heritage, looming medieval

ramparts, Georgian façades and the revolutionary community library ‒ a former church building

built in the ‘Brutalist’ style. The warm sunshine and the weightless buoyancy speeds me towards

euphoria. My mood soars like a bird rising on a thermal current of air. The canoe skims past the

junction to the Barrow Line canal. Memories of my previous canal voyage fizz to the surface: the

humiliating capsize, the bare-knuckle boxers, fast food hallucinations and the otherworldly

environment of Pollardstown Fen. But there’s no time to reminisce. There’s a weir straight ahead,

and the river has intentions of dragging the canoe straight over the falls.

‘Keep close to the bank,’ shouts my father, who has materialised beside me on the towpath,

wheeling along on his bike. The weir curves in a wide arch out from the opposite shore. The pull is

surprisingly strong, and the roaring falls overwhelms all other sound as I skirt along its lip. Most

canoeists shoot the weirs, as the falls are at a gentle incline and the drop is never more than two

metres. It’s a fun experience that comes with a small adrenaline rush, and it’s the easiest way to

avoid the challenging lock portages. If I was paddling a robust fibreglass canoe, I would happily

choose this option, but Minnow isn’t built for weirs; her thin plywood hull would splinter on the

hidden rocks and boulders. I researched the possibility of ‘lining’ the canoe over the weirs ‒

attaching a long rope to the stern and feeding the hull over the falls ‒ but this seemed an equally

risky business, destined to end in tears. It was back to my nemesis, portaging, for the time being.

Safely past the weir, I peel away from the river and guide the canoe into a lateral canal

towards Ardreigh, the first river lock. The still water is treacle-thick, overgrown and dense with

weeds. Within minutes I’m huffing and puffing through a tangle of slippery water lily stems and

trailing long fronds of pondweed. At the entrance to the lock I meet an early challenge ‒ how to

climb ashore? Squinting up at the ‘bikers’ standing silhouetted high above on the quayside, I realise

I haven’t a hope of scaling the wall, and am forced to retrace my way back up the canal in search of

an easier egress. Where the bank is slightly lower, I scramble ashore, strong-armed up by my father.

Between the two of us we carry the canoe along the towpath and around the lock, while my mother

fetches and carries my gear. With twenty-one more locks ahead, clearly this is going to be a slow

journey, requiring no small team effort! Sobered by the experience, we decide to raid the picnic

panniers, tucking into flapjacks washed down by scalding mugs of whiskey-laced coffee. Then it’s

off to rejoin the river just below the lock, a challenge as we hack a way through nettles and cling

perilously to clumps of weeds. It will be a miracle if I survive the journey without a few dunkings.

The river is in sparkling form ‒ energised from tumbling over the weir and rapids. Its

surface is littered with blobs of foam that spin like whirling dervishes in the fast-flowing current.

The canoe joins the flow and is whisked along at warp speed; at least it feels that way to me. For a

time, I manage to keep up with the bikers, who are travelling at full tilt on the towpath. As the

channel widens and deepens, the river relaxes. When I look up, the bikers have disappeared, leaving

me alone on the water. I rest the paddle across the gunnels and let the canoe drift. This is the release

I’ve been craving, and I want to savour it. The past few months have seen us all trapped on a roller-

coaster ride of anxiety, fear, sadness and frustration. Locked down at home, it was impossible to

avoid the wall-to-wall media coverage of the unfolding pandemic. The constant narrative ground

you down and set your nerves on edge. Now, out here on the river, I feel as though I have slipped

that world and entered a parallel universe. A far brighter world charged with optimism and wonder.

A sudden flash from the bank, a tiny fireball of gas-flame blue, streaks across Minnow’s

bow. Taken by surprise with a gasped intake of breath and paddle frozen in mid-air, I follow the

bird’s hurried flight path. There was a time when I kept a headcount of every kingfisher I saw, but

somewhere, back along the Grand Canal, I gave up when they became a commonplace occurrence.

This is my closest encounter yet, almost a collision. The bird was equally surprised; startled in

flight, it fluttered briefly, banked sharply, collected itself and fled crying downriver. In the

breathtaking moment as it tumbled over the canoe, I experienced its kaleidoscopic colours, from the

burnt orange of its breast to the iridescent blues of its back and wing feathers.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.